An enslaved African who lived at the Tower of London

Edward Francis was an enslaved African who poisoned his owner Thomas Dymock, the Keeper of the Lions at the Tower of London, in the late 1600s in a bid to gain his freedom.

This extraordinary story sheds new light on slavery and resistance at the Tower of London, as well as the broader context of slavery in English law and society.

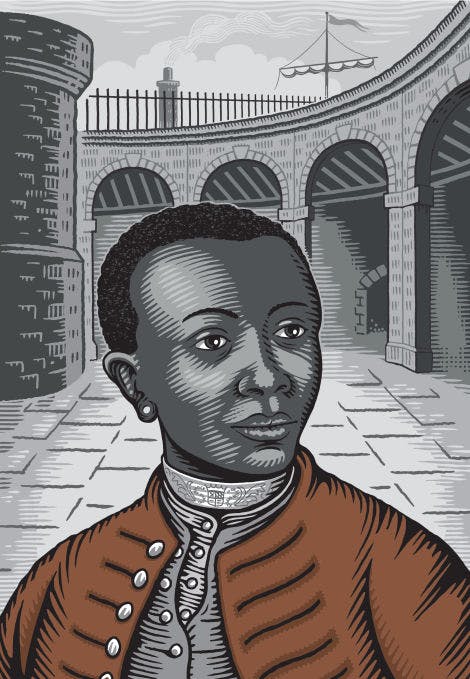

Header image: Illustration of Edward Francis, © Historic Royal Palaces

Image: The Examination and Confession of Edward Francis, 16th January 1691/2, London Lives, London Metropolitan Archives

Edward poisons the Dymocks

In January 1692, Thomas Dymock, the Keeper of the Lions at the Tower of London, appeared before Lord Lucas, the Constable of the Tower, to allege that ‘his Black’, a man named Edward Francis, had poisoned his household in order to ‘be master himself’.

Astonishingly, Edward Francis confessed. He admitted that he had begun poisoning Thomas Dymock and his wife Jane with rat poison, bought from a ‘rat catcher’, in the summer of 1691.

He had been told by another Black man named Tom, who lived on Mincing Lane in the City of London, that rat poison would make whoever took it ‘sick and vomit’.

Edward was unable to write his name, but at the bottom of his confession he scratched his 'mark' (in red).

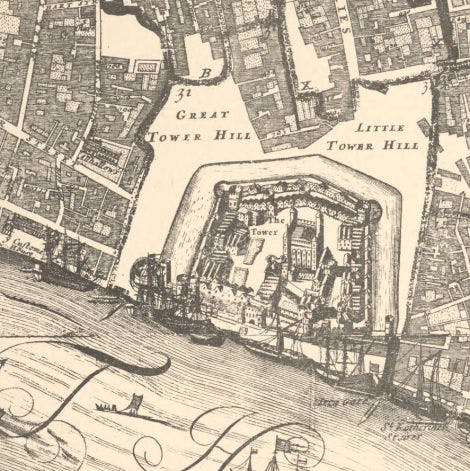

Detail of the Tower of London in Morgan's Map of the Whole of London in 1682. The Lion Tower is visible (crescent shaped structure) at the bottom left of the Tower. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Jane Dymock's death

Jane Dymock was already ill when Edward poisoned her, and she later died.

Jane was initially buried at the Tower's Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula on 11 July 1691, before she was later reburied at the Dymock family's church at St Vedast Foster Lane.

Thomas remarried a woman named Rebecka, whilst Edward continued putting poison in their food and drink throughout the summer and winter of 1691.

Why did Edward poison the Dymocks?

Edward’s actions demonstrate the extreme lengths that some people went to in order to resist enslavement.

The testimony given by Thomas and Rebecka clearly details that Edward hoped to gain his freedom by poisoning them both.

In a heated exchange, Thomas testified that Edward admitted putting poison in the food to murder him.

'What hurt have I done you,' Thomas challenged Edward, 'that you would be so bloody to kill me?'

When Edward was silent, Thomas pressed him: 'Did you think to get your liberty by killing me?' and apparently Edward answered 'yes'.

Rebecka's testimony was also revelatory.

She said Thomas scolded Edward that ‘he had deserved hanging long before for breaking locks and many thefts’.

Why would Edward break locks unless attempting to escape his imprisonment? The poisoning was not—it seems—the first time Edward tried to free himself from slavery.

We don't know when Edward Francis came to reside in Thomas Dymock's household, or how many times he attempted to gain his freedom, but there are a few clues.

An enslaved boy escapes the Tower

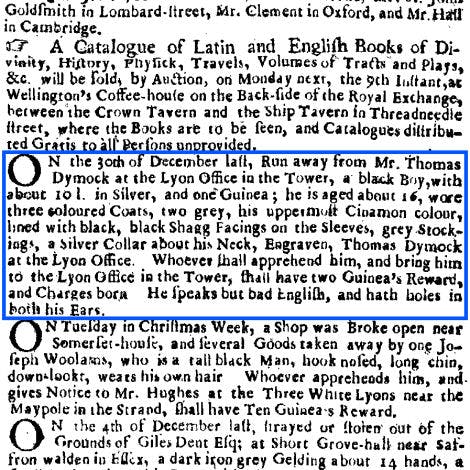

Four years earlier, on 30 December 1687, a 16-year-old enslaved African boy escaped from the Lion Tower. After two days of evading capture, Thomas Dymock posted an advertisement in the London Gazette, providing a description of the unnamed boy and offering a reward to secure his return.

According to the notice, the boy was clothed in three coats (two grey and one ‘cinnamon’ coloured) and grey stockings. He had also taken with him £10 in silver and one Guinea coin, worth about £1,300 in today’s money.

He also wore a silver collar around his neck, engraved with the words ‘Thomas Dymock at the Lion Office’. He was described as speaking ‘bad English’ and having ‘holes in both his ears’, indicating he was African-born and recently sold into slavery.

Collars

Enslaved people were sometimes made to wear collars to signify their ownership as human property. Such collars are described in newspaper notices and seen in contemporary portraits of Black servants.

Image: Detail of the London Gazette, issue 62309, 2-5 January 1687/8

'Runaway' advertisements

Over 800 newspaper advertisements like this were printed in Britain during the 17th and 18th centuries, offering rare glimpses into the lives of enslaved women, children, and men who desperately tried to gain their freedom.

Some slave-owners threatened that whoever dared to harbour or conceal fugitives did so at their own peril and could face prosecution.

Image: Illustration of Edward Francis at the Tower of London. He is depicted with an engraved collar. © Historic Royal Palaces

Was this Edward Francis?

The boy had clearly thought through his risky escape: he had wrapped up for the cold winter weather and stole a significant amount of money. His intention may have been to use it to pay someone to file off his collar or even board a nearby ship to aid his escape.

We don’t know whether this boy (whose name isn’t recorded) was captured and brought back to Thomas Dymock. But we do know that only four years later, in 1691, there was an enslaved man in Thomas’ household and his name was Edward Francis.

It’s possible that the boy who made a daring bid for freedom was Edward. Rebecka Dymock’s testimony certainly suggests that Edward and the 16-year-old boy both tried similar means to escape imprisonment and enslavement at the Tower, including breaking locks and theft.

Who was Thomas Dymock?

Thomas Dymock was appointed Keeper of the Lions at the Tower of London menagerie in 1686, a prestigious role he held until his death in 1704. By the winter of 1687, he had bought the enslaved boy who later ran away.

When he died, Rebecka took over the management of the Lion Office for a short period. Thomas was eventually succeeded by his son-in-law, William Gibson, the husband of his daughter, Elizabeth Dymock.

Slave trade

Enslaved Africans were not only trafficked into Britain, they were also bought and sold here.

Image: Today three lion sculptures mark the site of the former Lion Tower, named after the animals kept there. The Tower was demolished in the 18th century. © Historic Royal Palaces

Lions at the Tower Menagerie

At the menagerie, which operated from the 1200s until 1835, lions were an exotic spectacle as well as a symbol of royal power. It’s easy to imagine that owning an enslaved boy was, in Thomas’s eyes, another aspect of this unusual display.

Image: Portrait of a black page, head and shoulders, wearing a red cloak (oil on panel), Studio of Dyck, Anthony van (1599-1641). Portraits of Black servants frequently show them wearing a collar around their necks, an unmistakable indicator of their enslavement and treatment as human property. © Sotheby's / Bridgeman Images

Slavery in England

Enslaved Africans were considered property by their owners in England, even though slavery was not recognised in English law.

This meant that the status of enslaved people was often ambiguous and any degree of freedom they enjoyed was precarious. Being sold to English colonies, where slavery was codified in law, was always a threat.

It is difficult to estimate the exact number of enslaved Africans in 17th century England, as no official record was kept. However, newspaper notices seeking the return of fugitives, portraits, baptism and burial records suggest that slavery in England was not uncommon.

It wasn’t until 1834 that slavery in Britain and most parts of its empire was legally abolished.

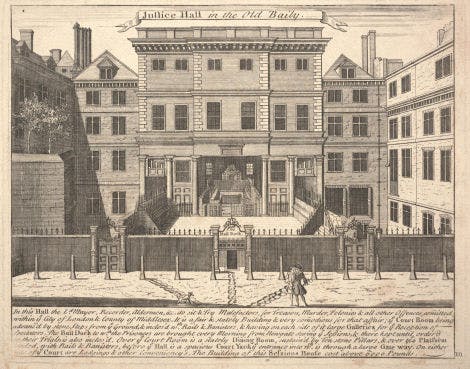

Image: Justice Hall in the Old Bailey, c1675 by an unknown artist. © Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts (Public Domain)

What happened to Edward Francis?

At the Old Bailey, Edward was tried and found guilty of a ‘misdemeanor’. He was imprisoned and fined ten groats, which had the value of around a day’s worth of wages for a skilled tradesman. In June 1692, after somehow managing to pay the fine, he was discharged from prison.

Why he was found guilty of the lesser offence of a ‘misdemeanor’ for poisoning the Dymocks, rather than attempted murder, is a bit of a mystery, but there are some possible explanations.

Possible theories

The English legal context, including Edward's status as an enslaved person, may help to explain why he escaped with only a fine.

Edward only admitted to wanting to make the Dymocks ill and there was no definite evidence that the rat poison had been the cause of Jane’s death.

There are also missing records from the Old Bailey in this period, meaning we do not have the full picture of what evidence was presented at his trial.

Edward’s status as Thomas’s slave may also have been significant. He was considered to be Thomas’s property—and valuable property at that.

As the victim, Thomas may have influenced the verdict on Edward’s crime and punishment.

It would not have served his interests to have Edward locked up for a long period of time or executed.

Whether Thomas took Edward back into his household and meted out his own punishment, sold him or set him free, is something we may never know.

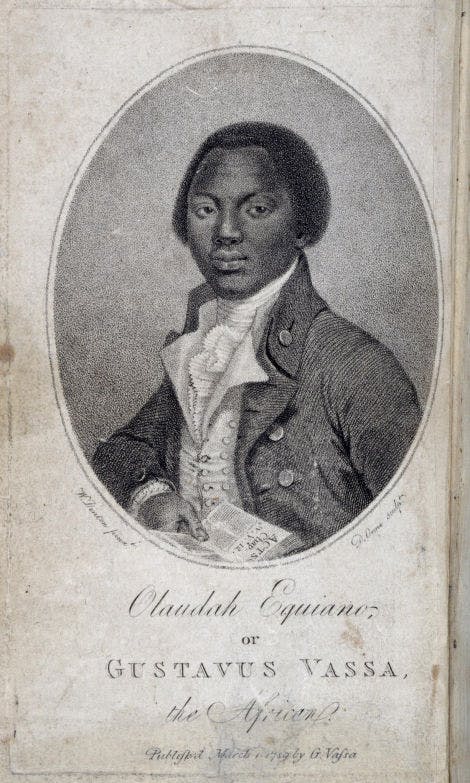

Image: Black and white portrait of Olaudah Equiano from 'The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano' (1789). © Alamy

Black Britons

In the decades following Edward’s trial, the population of Black Londoners continued to grow.

By the middle of the 18th century, there were around 15,000 Black servants in the capital. Some were free and earned wages, others were bound servants, and many were enslaved. There was also a growing free Black British population, who worked and lived in all kinds of settings .

Edward Francis was one of thousands of people of African descent in 17th and 18th century Britain, for whom the historical record is often very scarce. We know that there are other stories, like his, waiting to be told. By digging a bit deeper into the historical record, we can learn more about the rich history of Black Britons and their connections to our palaces.

Suggested reading

- Gerzina, G.H. (1995), Black London: Life Before Emancipation, New Brunswick: Rutgers

- Fryer, P. (1984), Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain, London: Pluto, repub. 2018

- London Lives

View of The Tower of London from the Thames

Unknown artist, c.1690-1710

This painting depicts the Tower of London, as it may have looked to Edward Francis in the 17th century. Looking at the Tower from the Thames, figures can be seen on the Tower wharf and there's a large British naval frigate with other boats on the river.

View the details of the painting below in high definition in this Gigapixel image.

Browse more history and stories

Coronations Past and Present

An ancient ceremony, largely unchanged for a thousand years

The Tower of London and the Second World War

Life at the Tower of London during the Second World War

The Tower of London and the First World War

The Tower of London played an important role in the First World War

Explore what's on

- For members

- Events

Members-only Ceremony of the Keys

Members-only access to the traditional locking up of the Tower of London, the Ceremony of the Keys.

-

13 July, 24 August, 14 September 2025

- 21:30

- Tower of London

- Separate ticket (advance booking required)

- Things to see

The Tower Moat

Take a relaxing stroll through the west side of the Tower Moat

-

Closed

- Tower of London

- Included in palace admission (Members go free)

- Things to see

Torture at the Tower exhibition

Discover stories of the unfortunate prisoners who were tortured within the walls of the Tower of London.

- Open

- Tower of London

- Included in palace admission (Members go free)

Shop online

Guy Fawkes Decoration

This luxury fabric hanging decoration commemorates the infamous attempt of Guy Fawkes to assassinate King James I during the State Opening of Parliament on November 5th, 1605.

£13

Crown of India Snow Globe

The Imperial State Crown of India, set with fabulous gems from India and other countries, is one of the heaviest crowns in the Crown Jewels collection with more than 6000 diamonds.

£15

Shop Hanging Decorations

Browse through our beautiful range of hanging decorations, ornaments and baubles including unique and hand-made pieces.

From £5.50